Press for 'Tokyo Girls'

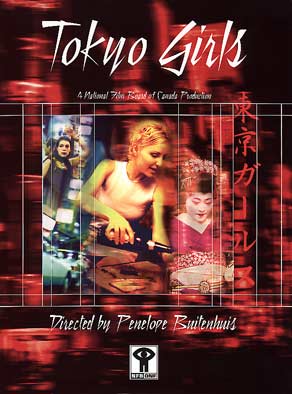

TOKYO GIRLS

ONF | NFB — l'OFFICE NATIONAL DU FILM DU CANADA

This feature documentary is a candid journey into the world of 4 young Canadian women who work as well-paid hostesses in exclusive Japanese nightclubs. Lured by adventure and easy money, these modern-day geisha find themselves caught up in the mizu shobai—the complex "floating water world" of Tokyo clubs and bars. Drawn by fast money, some women become consumed by the lavish lifestyle and forget why they came; one hostess calls this "losing the plot." With a pulsating visual style, Tokyo Girls captures the raw energy of urban Japan and its fascination with the new.

Vancouver film-maker Penelope Buitenhuis was surprised by what she found during the making of her documentary Tokyo Girls.

The companionship industry

A Vancouver director puts the camera on Japan's 'reverse exoticism.'

The Vancouver Sun, Saturday, September 30th, 2000

When Vancouver-based film-maker Penelope Buitenhuis toured the world in her 20s, she bonded with anarchists in Berlin and fell in with the art crowd in Paris- she even briefly flirted with the idea of becoming a hostess to rich Japanese businessmen after spending time with hostessing veterans in Southeast Asia.

"I was fascinated by their stories, but I just couldn't do it. I don't think I have what it takes to look interested when I'm not. I can't sit there and smile if someone is an idiot " says Buitenhuis, who also directed the Gemini-nominated Giant Mine.

Despite her reluctance to immerse herself in the hostessing world as a participant, Buitenhuis decided to do so as an observer and recently created Tokyo Girls, a National Film Board documentary about life in subcultures of paid drinkers, paid listeners and sometimes, paid bedmates to rich, lonely Japanese businessmen.

The film (which screens today at 9:30 p.m-, Robson Square) features several interviews with former hostesses and contains more than a few surprises as some of the paid conversations actually lead to genuine loving relationships.

Buitenhuis says she had a different idea in mind when she started the journey. I was hoping to capture the darker side of the business - the yakuza connections and the more sordid stuff, but the spy-cams we were using didn't work well in low light so we had a lot of footage of just glowing lights in black frames without many people. For a while, we started choosing our locations just on light levels," she says.

"When stuff like that happens it forces you to find creative solutions. You can often get a better film out of it because you have to embrace the material a a different level. In our case, we decided to take a more metaphorical approach to deal with what we couldn't see, and I think it really worked.

Buitenhuis says she discovered a form of 'reverse exoticism in Japan where white women are seen as strange beauties, a phenomenon that seems all the stranger when she interviews a white Canadian male addicted to the whole Geisha lifestyle.

"I didn't want to make my moral judgments about these people, because I think judgments are pointless and unfair. All I really wanted to capture was who these people were and how they approached this very strange job," says Buitenhuis.

"The one thing that really hit me in the process of making this film was just how removed we've become from one another. We're isolated and alone, so of course, things like hostess clubs and chat lines will emerge because the only thing that really makes us human is emotional connection to other people. Somewhere along the way, we've confused that with the unholy commodity of sex.

— Katherine Monk

The way Vancouver filmmaker Penelope Buitenhuis sees it, Western women who work in Japan’s lucrative hostess trade are opportunists who fill a human void in an alienated society, she tells ALEXANDRA GILL

From the Globe and Mail, Monday, April 2, 2000

When Penelope Buitenhuis went to Tokyo in 1999 to make a documentary about Western women who work in the hostess club trade, Lucie Blackman probably hadn’t even arrived in the crowded neon-lit city, where men pay hundreds of dollars to sit with pretty young women who smile, stroke their egos and pour them $50 shots of Scotch.

The story of the 22-year-old British airline attendant, however, begins very much the same way as many of the women Buitenhuis met for Tokyo Girls. Like Hilary, a fresh faced blonde from Vancouver who is featured in the film, Balckman went to Japan with the intention of working as a highly paid bar companion for three months to pay off her student debts. Unlike Hilary, Balckman never went home.

In February, seven months after Blackman had phoned a friend to say she was going on a seaside drive with a client and then vanished, her body was found in eight concrete-encased pieces buried in a cave on a beach near Tokyo. A 48-year-old property tycoon, Jyoji Obara, was arrested in October after an unidentified Canadian woman came forward, alleging she had been drugged and raped by him three years earlier. Obara had already been charged with raping five foreign and Japanese women who worked at hostess clubs in the Ropongi bar district. Since the grisly discovery of Blackman’s body, several other cases of missing hostesses, including a young woman from Calgary who disappeared three years ago, have surfaced. And the sordid side of this once-innocuous trade that attracts thousands of recruits from all over the world has undergone much public scrutiny.

When the National Film Board documentary airs tonight on CBC Newsworld’s The Passionate Eye, a postscript will be added to highlight the tragedy. But it was included at the CBC’s insistence. Because although Buitenhuis is sympathetic to Blackman’s family, and her film tells the story of one woman who got involved with a gangster and eventually had to flee Japan fearing for her life, she still thinks hostessing is a fairly safe profession.

“When something terrible happens, everyone goes ‘bad, bad, bad, bad, bad’” says Buitenhuis, a 40-year-old filmmaker who lives in Vancouver. “But terrible things can happen to women here when they’re walking down the street. I don’t agree with the fear-mongering going on in the media.”

Buitenhuis says she’s not trying to gloss over the dangerous elements of the trade or deny that the girls who get lured in by prospect of making upward of $3, 000 a month should be careful. But she says “weird things” can happen in any occupation. “They’ve proven that all those different women were raped by the same guy. So it is horrible. But that doesn’t make the entire occupation a danger zone. I’ve known tonnes of women from around the world who have done that job and nothing has happened to them.”

Rather than portraying the women in her film as vulnerable victims, Buitenhuis presents them as opportunists blatantly taking advantage of an old and often misunderstood Eastern tradition that has evolved into a modern-day business transaction. Hostesses, the way Buitenhuis sees them, are economy-class geishas that fill a human void in an alienated consumer society. And what compelled her most about the subject was the psychological impact of selling something more subtle and complicated than sex -- the charade of affection and friendship.

“ My intention with Tokyo Girls, “ she explains, “ was to get people to think: Would they do something like that if presented with the opportunity? I want the audience to really question their values. Would they do it for the money?”

Buitenhuis was inspired to make the film 10 years ago, while traveling through Asia for a film about male prostitution. Everywhere she went, she says, she met women who worked as hostesses.

“ What was most interesting for me was that sex costs less than a hostess. What is going on in this world where company is worth more than sex? This alienated society that is desperate for conversation and contact and romance?”

The concept made more sense to Buitenhuis after she visited a host club, where men paid to sit and chat with wealthy women. “I have to say I really enjoyed it. It felt pretty nice to be taken care of, looked after, told that you’re beautiful and make jokes and have fun. It’s pampering. And when do we get pampered by another human being who’s not a masseuse or something?”

The experience, however, exposed yet another disturbing side to this romanticized notion of intimacy. “A lot of the women treat the men like shit. There are a lot of lonely, disempowered wealthy wives in Japan. And it’s a power trip for them to go to a host club.”

Power is also an issue for some of the hostesses interviewed in the film. Nancy, a 24-year-old Montrealer, went to Japan to study contemporary dance but soon found herself working the bars. “I always have to insist that I’m not a prostitute,” she says. “It’s the mentality of old Japanese men with lots of money who think anything’s allowed.”

“There are a lot of women who can’t play a game, “ Buitenhuis says. “They can’t flirt with a guy and tell him he’s handsome. I think there’s a lot of women who can’t do it and they shouldn’t. They would feel compromised. You have to understand that you’re going to have to be a sweet little girl and it might be humiliating and you might hate it. But that’s the deal.”

STORIES BY FIONA MACDONALD

I'm good at sex,". says Leo- nominated, director Penelope Buitenhuis.

This area of expertise must have come in handy for the filming of the erotic thriller Dangerous Attraction. Buitenhuis was hired on for the film, which she says is "about a woman in lust and in love with two characters who are the same man. The woman is the main character - it's all about her dealing with her sexuality; she's a straight-laced girl and she goes on a bender. Shes in love with one character because he's so good, his passion is slow and not consummated, and she's in lust with the bad boy and their passion is consummated numerous times on screen. It's the same actor playing both characters and you really can't tell. The whole accent, body language and character is different

"It's very sexy and there's a fair amount-of violence. Part of the reason they hired me is that I'm good at sex, That's what I do."

In fact Buitenhuis spoke about her Leo nomination in the midst of shooting for her next film, Tokyo Girls, about Western women who work as hostesses in Japan. "It's about temptation," she says of the film that tracks four Canadian women, some of whom succumb to the seedy side of life in Tokyo. She also seems .to have a fondness for rock 'n' - roll having just secured funding' from B.C. Film "to rewrite my script Punk Not Dead. It's about a punk who's been preserved in beer for 20 years."

Of her Leo nomination Buitenhuis says "I'm surprised a little bit because (the film) is not standard fare but I'm thrilled.

Buitenhuis was drawn to the project for both its erotic content and by the idea of one actor convincingly portraying two utterly different personas. "I liked the idea of one character playing two roles because I wondered if I could pull it off. It was a challenge. And I like doing sex scenes, and there were quite a few of those. I also wanted to see if I could frighten people."

She appears to have succeeded and says the audience for the premiere "seemed to be scared in all the right places."

Hôtesse au Japon

FROM LA PRESSE, MONTREAL, MERCEDI 19, SEPTEMBRE 2001

MATHIEU PERREAULT

À LA FIN de ses études à l’École nationale de théâtre, Nancy Perron à reçu une bourse pour un stage à une célèbre école bhuto au Japon. À l’automne 1999, elle est débarquée à Tokyo, pleine d’enthousiasme à l’idée de se plonger dans cette danse traditionelle, dont elle avait eu un aperçu durant ses études.

Rapidement, elle a déchanté: sa bourse de 11 000 dollars ne lui permettrait jamais de vivre six mois dans l’une des villes les plus chères au monde, même si l’ambassade canadienne l’avait aidée à se trouver une chambre dans une résidence pour étudiants étrangers. Après quelques semaines, elle s’est rendue à la suggestion de copines de la résidence et est allée demander du travail dans un bar à hôtesses, dont les clients paient pour discuter avec des femmes, et qui tombent très rarement dans la prostitution.

<<J’avais entendu parler de ça avant de partir, mais je n’avais pas pensé que j’en aurais besoin>>, explique la comédienne montréalaise de 28 ans, en entrevue dans un café de la rue Stanley. Pendant quelques mois, elle a travaillé trois soirs par semaine dans un bar de Ginza tenu par une ancienne artiste, qui traitait bien ses employées. Elle se faisait plusieurs milliers de dollars par mois.

Ses clients payaient plusieurs centaines de dollars pour discuter avec elle une heur ou deux, en englais. Elle leur servait à boire, riait à leurs plaisanteries, flattait leur ego. <<Une femme peut se tenir très valorisée d’être toujours belle, bien maquillée, bien habillée. Ça a quelque chose d’apaisant. Des fois des clients envoyaient des caisses de parfums ou de maquillage au bar. Tu te sens plus femme d’être autant convoitée, mais en même temps tu te demandes pourquoi. Après quelque mois, j’étais écoeurée. Comme la plupart des autres, je buvais beaucoup pour que le temps passe plus vite. J’étais tannée de me sentir illégale, de dire à mes amis du bhuto que je travaillais dans un restaurant français.>>

Régulièrement, des clients lui disaient abruptement de parler moins, ou lui prenaient le micro de karaoké sans ménagement. <<Il fallait que je continue à sourire, que je lui dise <<Vas-y mon grand>>. Parfois des clients saouls commençaient à me parler de sexe dans l’oreille. Je leur disais tout de suite, sans cesser de sourire: <<Mettons les choses au clair: on ne parle pas de sexe. Sinon je m’en vais.>> Il ne fallait pas que la patronne m’entende être bête avec les clients; il fallait qu’ils soient toujours contents. Mais les clients de ce bar-là étaient de riches hommes d’affaires souvent galants. Jamais je n’ai eu de problèmes. Devoir régulièrement mettre les choses au point sur le sexe e endurci mon caractère.>>

Une seule fois, se souvient Mme Perron, un client qu’elle reconduisait à l’ascenseur a dépassé les bornnes: il a levé sa jupe et pincé ses fesses. <<Ma patronne lui a dit: <<Traite pas mes filles comme ça.>> C’était bien pire dans un autre bar où j’ai travaillé deux semaines, pour amasser de l’argent pour partir en voyage. C’était à Roppongi, un quartier où les clients ont moins d’argent et sons moins respectueux. Les filles acceptaient bien plus souvent des rendez-vous pour souper avec des clients. Une fois, un client de Roppongi a essayé de faire une passe. Comme la patronne ne regardait pas, je l’ai poussé dans l’ascenseur. Il s’est cogné la tête.>>

Un autre client au bar de Ginza a réussi à trouver son numéro de téléphone personnel. <<En général, je disais au clients qui voulaient me voir à l’extérieur du bar que j’allais les appeler. Ou je leur donnais des rendez-vous où je n’allais pas. J’étais hypocrite. Avec certains, j’ai accepté de correspondre. Je leur écris encore. Il y en a un qui voudrait passer par Montréal pour qu’on aille souper, une fois qu’il aura un rendez-vous aux États-Unis. Au Japon, il me prêtait des livres, des disques.>>

L’expérience de Nancy Perron a fait partie d’un documentaire de l’ONF, Tokyo Girls. La réalisatrice Penelope Buitenhuis a recontré trois autres Canadiennes. L’une d’entre elles a accepté de sortir avec un de ses clients qui l’a tellement couverte de cadeaux qu’elle a accepté de coucher avec lui. Rapidement, elle s’est rendu compte qu’il faisait parte des yakuza, les redoutables mafias japonaises. Prise de panique, elle a vidé son compte en banque des dizaines de milliers de dollars qu’il lui avait donné et s’est cachée plusieurs mois dans une île de Thaïlande. En 1999, une Canadienne qui travaillait comme hôtesses à †okyo a été assassinée par un de ses clients.

Nancy Perron ne pense pas que les bars à hôtesses ont perverti ses rapports avec les hommes. Elle a rompu avec le chum japonais qu’elle s’était fait à Tokyo, un étudiant de philosophie qui avait du mal à accepter son travail. Mais elle pense que son travail n’est pas la seule cause de sa rapture: il voulait contrôler sa vie en général, comment elle s’habillait par exemple. <<Je suis habituée à une égalité entre les hommes et les femmes>>, explique Mme Perron. Elle admet cependant qu’elle est souvent déçue par le manque de galanterie des Québécois.

la geisha venuta da occidente

iO donna, March 2001

DI PAOLA PIACENZA

<<All’inizio non avevo idea che questa esperienza avrebbe cambiato tutta la mia vita. Non potevo credere che mi pagassero solo per sorridere e bere>>. Mille dollari, per sorridere e bere. Tanto Jamie, bionda belleza canadese sui trent’anni, guadagnava come “hostess” nei club di Tokyo negli anni del boom economico tra il ‘91 e il ‘93. <<Da principio non sai bene cos’è. Senti che non è normale che gli uomini paghino per bere con te e che tu non abbia la libertà di andartene se la compagnia non ti va o se la conversazione non è interessante. Poi ti abitui. Il denaro genera assuefazione>>.

Hilary, 24 anni, bionda, carina, di Vancouver, da sei mesi hostess tra i vari “Lady’s room”, “Playhouse”, “Casanova club” e “Gentlemen’s club”, è richiestissima dalle mama-san, le rclutatrici di bellezze occidentali di Ginza, il quartiere del divertimento di Tokyo: <<Farsi vedere con una ragazza bionda e alta giova all’immagine dgli uomini d’affari nipponici, significa possedere qualcosa di raro, qualcosa che difficilmente il giapponese medio può avere>>.

Nancy Caroline Perron, 27 anni, alta, mora, è arrivata a Tokyo da Montreal da pochi mesi, per seguire un corso di “butoh”, una danza giapponese contemporanea. La vita della capitale, però, si è rivelata troppo costosa per il suo budget e lei si è ritrovata a fare la hostess per pagarsi gli studi. Ma a casa ha raccontatoche fa la cameriera: <<So che gli uomini qui mi cercano solo perché sono bianca, occidentale e, visto che parlo francese, chic. So che il lavoro non è considerato rispettabile, anzi, decisamente illegale. Rientra nella categoria dei “Mizu shobai”, business dell’acqua fluttuante, lavori “non onorevoli”, ma tollerati finché chi li fa riesce a passare inosservato. E in questo io sono diventata abilissima>>.

Dhana ha fatto la hostess per sei anni, poi si è sposata con uno dei suoi “clienti” che, per convincerla, anziché un anello, le ha offerto un millione di dollari: <<So che in Occidente può suonare strano, ma un’offerta del genere è perfettamente in linea con la cultura giapponese, è più naturale per un businessman condurre in porto un buon affare che fare una dichiarazione d”amore. Ci siamo sposati nel 1995 e due anni dopo è nata nostra figlia>>.

Dhana, Nancy, Hilary, Jamie sono solo alcune delle protagoniste di Tokyo girls, film-documentario della regista canadese Penelope Buitenhuis, passsato recentemente ai festival Biarritz, di Montreal e a quello del cinema delle donne di Torino, sul fenomeno delle “hostess”, le giovani accompagnatrici occidentali che hanno definitivamente sostituito le “geishe”, le tradizionali donne di compagnia dagli innumerevoli talenti, canto, danza, conversazione, poesia, frutto di un training durissimo e prolungato. Proprio mentre Steven Spielberg si appresta a rinverdime i fasti con il suo Memoirs of a geisha, tratto dal romanzo di Arthur Golden, con Maggie Cheung e Rika Okamoto nei ruoli principali.

Io donna ha incontrato la regista di Tokyo girls che, nella capitale giapponese, ha passato sette mesi indagando le radici del fenomeno.

Dal Canada a Tokyo in cerca delle “nuove geishe”. Com’è cominciata?

<<Avevo sentito parlare delle “hostess” durante i miei viaggi in Oriente. Chi le aveva conosciute mi diceva che si trattava di ragazze intelligenti, colte, molto lontane dall’idea dell’accompagnatrice-prostituta che abbiamo in Occidente. Queste donne hanno cominciato a costituire una specie di mistero, soprattutto perché nella nostra società non c’è familiarità con l’idea della compagnia di una donna a pagamento, ma senza sesso. In Nordamerica è un fenomeno sconosciuto, comincia a prendere piede in Inghilterra e in Germania, ma è quasi sempre connesso al sesso. In Giappone invece ha avuto risvolti inaspettati: contribuendo ad archiviare le tradizionali geishe perché, anche se si tratta di un servizio molto caro (sicuramente molto più di una prostituta), una hostess non costerà mai quanto una geisha>>.

Cos’hanno in commune la geisha tradizionale e la moderna hostess?

<<Svolgono compiti simili sotto due aspetti, quello delle relazioni umane e quello sociale-professionale. I rapporti umani in Giappone, anche se stanno evolvendo sotto la spinta delle influenze occidentali, sono ancora molto difficili. I matrimoni sono raremente unioni d’amore e gli uomini, sotto-posti a mille pressioni sul lavoro, arrivano spesso a un punto in cui sentono il bisogno di qualcosa di romantico nella propria vita: le geisha e le hostess sono entrambe figure perfette per questo scopo, non comportano coinvolgimenti sentimentali eccessivi non costano come un’amante vera, fuori portata anche per i businessman. D’altro canto il sistema dei rapporti sociali in Giappone è molto rigido, concludere un affare può richiedere anni a causa del formalismo esasperato. Per questo i businessman passano la maggior parte del tempo coltivando relazioni, hanno bisogno di tempo per “scaldarsi”. In passato, le geishe servivano proprio a questo: ad ammorbidire l’atmosfera. Le moderne hostess fanno lo stesso, soprattutto quando si devono concludere “affari sporchi”>>.

Perché i giapponesi di oggi sono più attirati dalle donne occidentali che dalle loro connazionali? Razzismo o complesso d’inferiorità?

<<Il razzismo, l’idea della razza superiore giapponese, è presente solo tra gli uomini più anziani: alcuni di loro mi hanno confessato che aver perso la guerra per loro è un’onta tale che “avere” una donna occidentale può costituire una sorta di riscatto. Aiuta a smaltire l’odio per l’Occidente, soprattutto verso l’America. Ma per i più giovani è diverso: pagano una hostess perché sanno che non avranno mai la possibilità di parlare a una donna occidentale, perché non viaggiano, non sanno l’inglese e sono repressi. La maggior parte delle ragazze, infatti, deve limitarsi a sorridere, al massimo sostenere una conversazione. L’importante è farsi vedere>>.

E davvero il sesso non c’entra?

<<È difficile fare statistiche su quanti di questi incontri finiscano a letto. La tentazione del denaro facile fa sì che talvolta alcune ragazze decidano di fare sesso con i clienti, cosa che nei loro Paesi d’origine probabilmente non avvrebero mai fatto. La mia opinione, visitando i club, è che molto dipenda dall’atmosfera del locale: alcuni decisamente scoraggiano il sesso con i clienti, altri sono più tolleranti. Credo che non più del 5-10 per cento degli incontri finisca in camera da letto, ma è un’approssimazione perché pochissime ragazze l’hanno ammesso, non è una cosa di cui vanno fiere>>.

Capita che le ragazze si trovino in situazioni rischiose?

<<Una delle donne che ho incontrato mi ha raccontato di avere avuto come cliente fisso per un periodo uno yakuza, un mafioso: le regalava gioielli e le lasciava grosse mance. Un giorno la mama-san le ha detto: “Ma tu sai chi è quell’uomo? Non puoi continuare ad accettare i suoi regali. prima o poi ti chiederà qualcosa in cambio”. Quella ragazza ha dovuto andarsene per un po’, per far perdere le proprie tracce. Ma sono le thailandesi e le filippine a rischiare di più, perché occupano un gradino più basso nella società ed è più facile sfruttarle>>.

Quanto guadagna una hostess?

<<Adesso non più tanto, per colpa della crisi economica. Ma molto dipende dalla sua abilità a far bere il cliente, perché le hostess hanno commissioni su ogni drink. Anche la notorietà del locale è importante, il più famoso è il “1 l Jack”, lì girano uomini molto facoltosi che lasciano grosse mance. Una ragazza australiana mi ha raccontato di essere capace di far bere sette-otto drink all’ora a 20-30 dollari l’uno. Lei guadagnava circa 600 dollari a sera. Le meno brave si devono accontentare di 200-300 dollari>>.

Quanto è diffuso il fenomeno?

<<È quasi impossible stlare statistiche, visto che si tratta di un fenomeno in gran parte sommerso. Mi è stato difficile persino scoprire quanti club ci sono a Tokyo: ho fatto un’approssimazione sulla base di un censimento della polizia per ragioni tributarie. Diciamo che ci sono 30-40 club con donne occidentali, ma migliaia di altro tipo. E il fenomeno è diffuso anche nelle altre maggiori città del Giappone, Kyoto, Yokohama. È cominciato alla fine degli anni Settanta, poi si è sviluppato in seguito, alla metà degli Ottanta. All’inizio era casuale, si trattava per lo più di viaggiatrici che facevano le hostess per pagarsi gli studi, i corsi di ballo o il bigletto di ritorno. Negli ultimi cinque anni, però, si sono create vere e proprie agenzie di reclutamento, in Canada per esempio ce n’è una>>.

Le geishe quindi sono condannate all’estinzione?

<<In Giappone c’è sempre meno interesse per la tradizione. Le geishe che si incrociano ancora oggi per le strade di Tokyo sono attrazioni turistiche. Esiste una scuola apposita per la loro formazione: imparano i movimenti base, a vestirsi, a truccarsi, quanto basta per passeggiare lungo le stradde della vecchia Tokyo e farsi fotografare dai turisti tra i templi. Le geishe sono scomparse molto tempo fa>>.

PAOLA PIACENZA